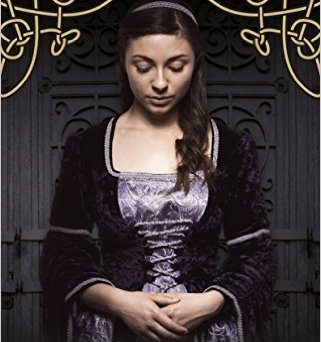

K. M. Ashman, In Shadows of Kings (Silverback Books 2014)

Rhodri ap Gruffydd, nicknamed Tarian (Shield of the Poor), has summoned his knights to a secret banquet. King Henry of England is dead, Edward Longshanks yet in the Holy Land, but more battles with the Welsh are in store on his return. Tarian and his knights are doubting the leadership of Prince Llewelyn.

At Brycheniog Abbey, Abbot Williams, the man who murdered Garyn’s parents, discusses the transport of the True Cross to Rome. Garyn ap Thomas, the blacksmith’s son, joins his wife Elspeth for dinner, exhausted from rethatching the roof. His brother Geraint, missing the camaraderie of the Crusades, is about to leave on a journey aboard a ship commissioned by Tarian.

Owen Cadwallader comes to the manor of the deceased Sir Robert Cadwallader to forge a marriage between Sir Gerald of Essex and the elder daughter, Suzette.

Father Williams and the newly betrothed Sir Gerald seem to have it in for Garyn’s family and livelihood, and he has to flee. He joins the Blaidd (Wolves) mercenaries to fight brigands. The rescue of a kidnapped girl brings new information about the True Cross, leading Garyn to realise that he had been double crossed.

Tarian’s flotilla disembark on a new world and battle with the natives, aided by the Mandan, a people who speak their language. They’ve come seeking the descendant of Madoc, who travelled three times to the New World.

The characters are lively, the dialogue credible and the plot exciting, alternating interestingly between Wales and the new World. The writing is just archaic enough to pass, but without any embellishments. This is Book 2 in the Medieval Series, and Book 1’s backstory of the retrieval of the True Cross and the persecution of Garyn’s parents is handled skilfully. It keeps the promise of the ‘direction you will not expect’ promised in the Foreword.

This review was originally written for Historical Novels Review.