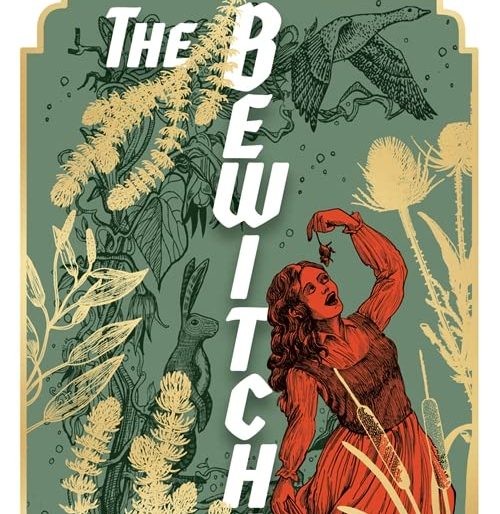

R. Jay Driskill, Kings of Stone (Kindle 2025)

Everything we know about the Hittites

The civilisation of the Hittites, who flourished 1650-1180 BCE in Anatolia, has been shrouded in mystery. Archaeologist Archibald Henry Sayce in 1872 was the first to recognise that the Anatolian carvings on stone represented a distinct, hitherto forgotten culture.

During the following centuries there have been a number of illuminating archaeological discoveries, notably the decipherment of their early Indo-European language Luwian, which had its breakthough with the discovery in 1946 of the ‘Hittite Rosetta Stone’, the 8th century BCE Karatepe bilingual inscription.

Hittite studies have been complemented by the Amarna letters from Egypt, Ugaritic archives from Syria and Mycenaean Linear B tablets.

Archaeologist Driskill outlines what we know about the Bronze Age superpower, from their origins in Anatolia 2300-2000 BCE [debated] to the zenith of their power in the 13th century BCE to their collapse during the Sea Peoples period. Suppiluliuma II (ca. 1207-1180 BCE) was the last documented Hittite king, but the capital Hattuša, intriguingly, was abandoned not destroyed.

They called their own language Nesili and themselves ‘people of the land of Hatti’, after the non-Indo-European non-Semitic Hattians, whom they had either assimilated or conquered and whose double-headed eagle symbol and chief deities they adopted. Some of the prayers and rituals were conducted in Hattian. Onomastic (placenames) evidence points to a bilingual culture, with borrowing from Sumerian and Akkadian. ‘Hittite cultural development was one of creative synthesis rather than… separation.’ With distinct cultural boundaries (gods were localised) but with extensive borrowing.

The Hittite Law Code 1650-1500 BCE, as compared to its harsher contemporary Code of Hammurabi, stressed compensation rather than ‘eye for an eye’ punishment. Their pragmatic and accommodating approach to statecraft and diplomacy established precedents across the ancient world. They played a pioneering role in the development of iron (which they called ‘black metal’) metallurgy.

It charts the history century by century—dry, academic stuff, kings and dates and footnotes, but if you want to learn about the Hittites, it does the business in a cogent style. It goes through it all, language, kingly succession, governmental structures, religious pantheon, trade, agricultural practices and cultural and artistic trends.

I love how each chapter, representing a particular period, is illustrated by a choice artefact. They are in colour, but I wish the photos were a bit larger, and I would like to have read a description of the object, where it was found etc.

I received an advance review copy for free, and I am leaving this review voluntarily.